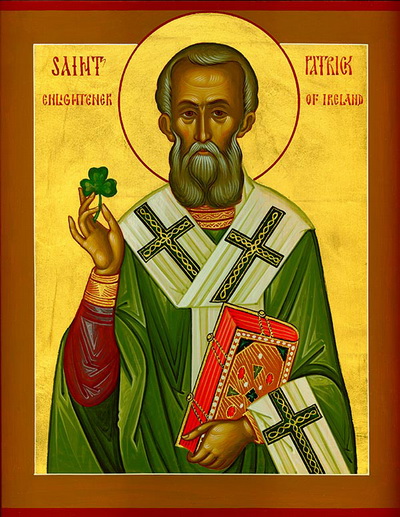

"On Mount Sinai, Abbot St. John Climacus."

St John Climacus (c525-606) is famous for his work The Ladder of Divine Ascent, which is traditionally read during Lent in Eastern monasteries.

Pope Benedict XVI gave a General Audience on him in 2009:

"...And I am proposing the figure of John known as Climacus, a Latin transliteration of the Greek term klimakos, which means of the ladder (klimax). This is the title of his most important work in which he describes the ladder of human life ascending towards God. He was born in about 575 a.d. He lived, therefore, during the years in which Byzantium, the capital of the Roman Empire of the East, experienced the greatest crisis in its history. The geographical situation of the Empire suddenly changed and the torrent of barbarian invasions swept away all its structures. Only the structure of the Church withstood them, continuing in these difficult times to carry out her missionary, human, social and cultural action, especially through the network of monasteries in which great religious figures such as, precisely, John Climacus were active.

John lived and told of his spiritual experiences in the Mountains of Sinai, where Moses encountered God and Elijah heard his voice. Information on him has been preserved in a brief Life (PG 88, 596-608), written by a monk, Daniel of Raithu. At the age of 16, John, who had become a monk on Mount Sinai, made himself a disciple of Abba Martyr, an "elder", that is, a "wise man". At about 20 years of age, he chose to live as a hermit in a grotto at the foot of the mountain in the locality of Tola, eight kilometres from the present-day St Catherine's Monastery. Solitude, however, did not prevent him from meeting people eager for spiritual direction, or from paying visits to several monasteries near Alexandria. In fact, far from being an escape from the world and human reality, his eremitical retreat led to ardent love for others (Life, 5) and for God (ibid., 7). After 40 years of life as a hermit, lived in love for God and for neighbour years in which he wept, prayed and fought with demons he was appointed hegumen of the large monastery on Mount Sinai and thus returned to cenobitic life in a monastery. However, several years before his death, nostalgic for the eremitical life, he handed over the government of the community to his brother, a monk in the same monastery.

John died after the year 650. He lived his life between two mountains, Sinai and Tabor and one can truly say that he radiated the light which Moses saw on Sinai and which was contemplated by the three Apostles on Mount Tabor!

He became famous, as I have already said, through his work, entitled The Climax, in the West known as the Ladder of Divine Ascent (PG 88, 632-1164). Composed at the insistent request of the hegumen of the neighbouring Monastery of Raithu in Sinai, the Ladder is a complete treatise of spiritual life in which John describes the monk's journey from renunciation of the world to the perfection of love. This journey according to his book covers 30 steps, each one of which is linked to the next. The journey may be summarized in three consecutive stages: the first is expressed in renunciation of the world in order to return to a state of evangelical childhood. Thus, the essential is not the renunciation but rather the connection with what Jesus said, that is, the return to true childhood in the spiritual sense, becoming like children. John comments: "A good foundation of three layers and three pillars is: innocence, fasting and temperance. Let all babes in Christ (cf. 1 Cor 3: 1) begin with these virtues, taking as their model the natural babes" (1, 20; 636). Voluntary detachment from beloved people and places permits the soul to enter into deeper communion with God. This renunciation leads to obedience which is the way to humility through humiliations which will never be absent on the part of the brethren. John comments: "Blessed is he who has mortified his will to the very end and has entrusted the care of himself to his teacher in the Lord: indeed he will be placed on the right hand of the Crucified One!" (4, 37; 704).

The second stage of the journey consists in spiritual combat against the passions. Every step of the ladder is linked to a principal passion that is defined and diagnosed, with an indication of the treatment and a proposal of the corresponding virtue. All together, these steps of the ladder undoubtedly constitute the most important treatise of spiritual strategy that we possess. The struggle against the passions, however, is steeped in the positive it does not remain as something negative thanks to the image of the "fire" of the Holy Spirit: that "all those who enter upon the good fight (cf. 1 Tm 6: 12), which is hard and narrow,... may realize that they must leap into the fire, if they really expect the celestial fire to dwell in them" (1,18; 636). The fire of the Holy Spirit is the fire of love and truth. The power of the Holy Spirit alone guarantees victory. However, according to John Climacus it is important to be aware that the passions are not evil in themselves; they become so through human freedom's wrong use of them. If they are purified, the passions reveal to man the path towards God with energy unified by ascesis and grace and, "if they have received from the Creator an order and a beginning..., the limit of virtue is boundless" (26/2, 37; 1068).

The last stage of the journey is Christian perfection that is developed in the last seven steps of the Ladder. These are the highest stages of spiritual life, which can be experienced by the "Hesychasts": the solitaries, those who have attained quiet and inner peace; but these stages are also accessible to the more fervent cenobites. Of the first three simplicity, humility and discernment John, in line with the Desert Fathers, considered the ability to discern, the most important. Every type of behaviour must be subject to discernment; everything, in fact, depends on one's deepest motivations, which need to be closely examined. Here one enters into the soul of the person and it is a question of reawakening in the hermit, in the Christian, spiritual sensitivity and a "feeling heart", which are gifts from God: "After God, we ought to follow our conscience as a rule and guide in everything," (26/1,5; 1013). In this way one reaches tranquillity of soul, hesychia, by means of which the soul may gaze upon the abyss of the divine mysteries.

The state of quiet, of inner peace, prepares the Hesychast for prayer which in John is twofold: "corporeal prayer" and "prayer of the heart". The former is proper to those who need the help of bodily movement: stretching out the hands, uttering groans, beating the breast, etc. (15, 26; 900). The latter is spontaneous, because it is an effect of the reawakening of spiritual sensitivity, a gift of God to those who devote themselves to corporeal prayer. In John this takes the name "Jesus prayer" (Iesou euche), and is constituted in the invocation of solely Jesus' name, an invocation that is continuous like breathing: "May your remembrance of Jesus become one with your breathing, and you will then know the usefulness of hesychia", inner peace (27/2, 26; 1112). At the end the prayer becomes very simple: the word "Jesus" simply becomes one with the breath.

The last step of the ladder (30), suffused with "the sober inebriation of the spirit", is dedicated to the supreme "trinity of virtues": faith, hope and above all charity. John also speaks of charity as eros (human love), a symbol of the matrimonial union of the soul with God, and once again chooses the image of fire to express the fervour, light and purification of love for God. The power of human love can be reoriented to God, just as a cultivated olive may be grafted on to a wild olive tree (cf. Rm 11: 24) (cf. 15, 66; 893). John is convinced that an intense experience of this eros will help the soul to advance far more than the harsh struggle against the passions, because of its great power. Thus, in our journey, the positive aspect prevails. Yet charity is also seen in close relation to hope: "Hope is the power that drives love. Thanks to hope, we can look forward to the reward of charity.... Hope is the doorway of love.... The absence of hope destroys charity: our efforts are bound to it, our labours are sustained by it, and through it we are enveloped by the mercy of God" (30, 16; 1157). The conclusion of the Ladder contains the synthesis of the work in words that the author has God himself utter: "May this ladder teach you the spiritual disposition of the virtues. I am at the summit of the ladder, and as my great initiate (St Paul) said: "So faith, hope, love abide, these three; but the greatest of these is love' (1 Cor 13: 13)!" (30, 18; 1160).

At this point, a last question must be asked: can the Ladder, a work written by a hermit monk who lived 1,400 years ago, say something to us today? Can the existential journey of a man who lived his entire life on Mount Sinai in such a distant time be relevant to us? At first glance it would seem that the answer must be "no", because John Climacus is too remote from us. But if we look a little closer, we see that the monastic life is only a great symbol of baptismal life, of Christian life. It shows, so to speak, in capital letters what we write day after day in small letters. It is a prophetic symbol that reveals what the life of the baptized person is, in communion with Christ, with his death and Resurrection. The fact that the top of the "ladder", the final steps, are at the same time the fundamental, initial and most simple virtues is particularly important to me: faith, hope and charity. These are not virtues accessible only to moral heroes; rather they are gifts of God to all the baptized: in them our life develops too. The beginning is also the end, the starting point is also the point of arrival: the whole journey towards an ever more radical realization of faith, hope and charity. The whole ascent is present in these virtues. Faith is fundamental, because this virtue implies that I renounce my arrogance, my thought, and the claim to judge by myself without entrusting myself to others. This journey towards humility, towards spiritual childhood is essential. It is necessary to overcome the attitude of arrogance that makes one say: I know better, in this my time of the 21st century, than what people could have known then. Instead, it is necessary to entrust oneself to Sacred Scripture alone, to the word of the Lord, to look out on the horizon of faith with humility, in order to enter into the enormous immensity of the universal world, of the world of God. In this way our soul grows, the sensitivity of the heart grows toward God. Rightly, John Climacus says that hope alone renders us capable of living charity; hope in which we transcend the things of every day, we do not expect success in our earthly days but we look forward to the revelation of God himself at last. It is only in this extension of our soul, in this self-transcendence, that our life becomes great and that we are able to bear the effort and disappointments of every day, that we can be kind to others without expecting any reward. Only if there is God, this great hope to which I aspire, can I take the small steps of my life and thus learn charity. The mystery of prayer, of the personal knowledge of Jesus, is concealed in charity: simple prayer that strives only to move the divine Teacher's heart. So it is that one's own heart opens, one learns from him his own kindness, his love. Let us therefore use this "ascent" of faith, hope and charity. In this way we will arrive at true life."