So far in this series I have canvassed the non-liturgical options around prayer.

In this post I want to talk about liturgical prayer in the form of the Divine Office.

The importance of liturgical prayer

The Divine Office plays little part in the lives of most modern Catholics.

Yet it should.

All forms of prayer can be good and effective. But liturgical prayer has a higher status than other forms of prayer. Dom Fernard Cabrol, first abbot of Farnborough, writing in 1915, explains it this way:

Private prayer has a personal value, varying according to the degree of faith, fervour, and holiness of he who prays. The Church's prayer has always, in itself, and independently of the person praying, an absolute value. It is a formula composed by the Church, and carrying with it her authority...Liturgical prayer is superior to all others not only because it is the Church's prayer but also because of the elements of which is composed...this prayer holds the first rank on account of its efficacy, or the effects it produces in the soul. (Introduction to Day Hours of the Church, vol 1)

And contrary to most of the emphasis of the last couple of centuries, the Mass is not the only thing that constitutes liturgy. Rather, the Divine Office, the 'Work of God', is intended to extend and support the effects throughout our day and week.

The importance and value of the Office is still upheld by the Church today, at least on paper. The 1983 Code of Canon Law for example says:

In the Liturgy of the Hours, the Church, hearing God speaking to his people and recalling the mystery of salvation, praises him without ceasing by song and prayer and intercedes for the salvation of the whole world.

In practice, though, it has all but disappeared. This is something we need to change!

The importance and value of the Office is still upheld by the Church today, at least on paper. The 1983 Code of Canon Law for example says:

Early history

The Divine Office has an ancient history: fixed times of prayers has Jewish roots, and was certainly practised in primitive form in the very earliest days of the Church.

Many of the Fathers point to the references to prayer at the third, sixth, ninth hours and in the night in Acts as the origins of this tradition.

Certainly very early Church documents indeed attest to the idea of regular prayer at set times: in the first century Didache mentions praying the Our Father three times a day, while the fourth bishop of Rome, Clement (died 99 AD), wrote of prayer at the appointed times and hours for example.

The Office in the life of the Church

Early Church documents clearly assume that the laity as well as the clergy would pray at set times through the day and night. That doesn't mean, though, that anyone has ever expected the laity to say all 150 psalms in a week at the Office, or say all the formal hours of the Office - far from it.

The tradition as far as I can see, has always been for the duty of praying the whole Office to be entrusted to monks and nuns (and to some degree the clergy), with laypeople joining in where possible and sensible. In the later Middle Ages in England, for example, parish priests were certainly expected to say Lauds and Vespers publicly on Sundays, and many joined in with this. But when it came to Matins (Vigils), if the people said it at all, they used one of the many short Offices, such as that of Our Lady.

All the same, the Office in many varied forms was an integral part of the life of the Church (including the laity) for many centuries, with more 'books of hours' produced prior to the Reformation, than any other single book.

The decline in the use of the Office

All that changed with the Council of Trent, when the need to combat the spread of heresy led to much tighter controls over the liturgy and devotions more generally.

One of the key changes made at that time was the restriction of the delegation to pray the Office liturgically to priests and religious. The effect of this was that the laity could only take part in the Office when it was led by a priest or solemnly professed religious.

Several other factors also probably contributed to the decline in the popularity of the Office.

The Office is fundamentally meant to be performed communally and sung. But the years after Trent favoured the 'low Mass' mentality deeply at odds with this.

The shift in Scriptural exegesis from the seventeenth century onward, from a focus on its spiritual meaning and in particular to seeing Christ in the psalms, to a focus on their historical and literary context instead, probably did not help.

Even so, in many places, attending Sunday Vespers at least was often regarded as nearly as mandatory as attending Sunday Mass.

Over time though, this tradition gradually fell away as priests in particular increasingly saw the Divine Office as an obligation that was rather burdensome to fulfil, rather than a source of spiritual fodder and solace.

Rebuilding the walls of Jerusalem?

The twentieth century saw a string of 'reforms' - from the Pius X psalter of 1911 to the Liturgy of the Hours of 1971 - ostensibly aimed at reviving the use of the Office. Unfortunately, they have mostly had the opposite effect.

There was, though, one positive reform that came out of Vatican II, and that was the restoration of the right of the laity to pray the Office liturgically.

Vatican II's Sacrosanctum Concilium made some rather ambiguous statements on the subject of the laity praying the Office that could perhaps be interpreted a number of ways.

Subsequent legislation, however, including the General Instruction on the Liturgy of the Hours, and more particularly the 1983 Code of Canon law (in turn reflected in the Catechism of the Catholic Church) has made it clear that the laity are now officially deputed to pray the Divine Office on behalf of the Church, even when praying in small groups without a priest, or by themselves.

This a wonderful privilege.

Laypeople face a considerable challenge, though, in actually exercising this privilege in that few churches or even Cathedrals actually regularly offer the Office publicly (head to most and you more likely to find an evening Mass than Vespers!), the Office is not taught in schools or parishes; and the books for the Office are not easy to use.

The 1971 Liturgy of the hours

The modern Liturgy of the Hours has the advantage for many, in being available in the vernacular.

But it is, as Laszlo Dobszay pointed out, a radically new product, not something in continuity with tradition: it abolished the characteristic structure of the Hours, abandoned the traditional principles for the distribution of the psalms and created something that is fundamentally a book to be read, not a communal office meant to be sung.

Older forms of the Office

The alternative is to use one of the older forms of the Office such as the 1962 Roman Breviary.

The problem is that, as far as I am aware, all of the pre-Vatican II forms of the Office still approved for liturgical use require it to be said in Latin - translations are available to

assist in understanding only.

That means anyone wanting to say the Office has to commit to learning at least how to pronounce the Latin adequately, and study the texts sufficiently to have at least a general sense of what they mean.

Even if you only plan on saying a few suitable hours - Prime and Compline for example, and perhaps Sunday Vespers (a more than adequate regime for most people) - that can be quite a few psalms to learn.

Little Office of Our

Lady

One possible option that minimises the learning curve is the Little Office of Our Lady.

The Little Office is not actually short - it takes as long to say or sing as the full Office.

But the psalms (apart from Matins) are the same every day, reducing the amount of learning involved while still providing a very satisfying source of prayer. In addition it has very few seasonal or festal variants, so does not require juggling ordos and finding texts from multiple places in a breviary. Moreover, for those who really want to say all of the hours (at least occasionally), it offers a very manageable option for Matins (three psalms each day) with some variety to it.

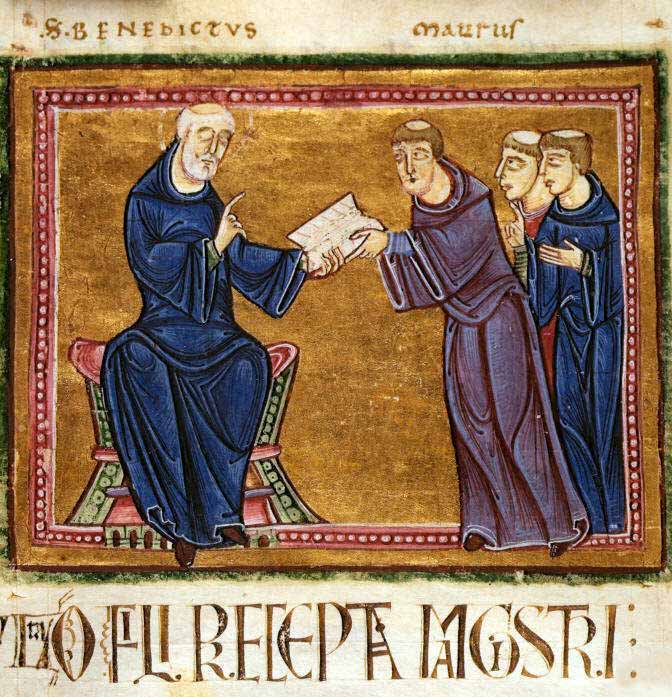

Then too, prayer honouring Our Lady is attractive in its own right: the Little Office has its origins in eighth century Benedictine tradition, but seems to have spread rapidly. For many centuries it was said by religious as well as the normal Office of the day. In more recent times it was used as a form of prayer by many religious in simple vows and by third orders.

The Baronius edition supplies the chants

necessary to sing it, and there are resources available around the web to help you learn to say it. It should be noted however that the Baronius edition is not actually formally approved for liturgical use in accordance with the requirements of canon law - so if you want to say it liturgically you would technically need to find a version that is, for example in a full breviary (the 1962 monastic breviary for example includes the Little Office). Of course, whether this really affects the validity of the Office (as opposed to the liceity) seems to me doubtful..

1962 Roman Office

The Little Office though, does lack variety, and many eventually want to use a wider range of psalms. The 1962 Roman Office is the next obvious step to consider.

It has a lot of advantages for traditionalists, not least that if you learn it you might be able to persuade your priest to lead Sunday Vespers (there may b a question about whether use of another rite or use will satisfy his obligation to say the Office).

There are guides on how to say it around, as well as Ordos such as the excellent one put out by the Latin Mass Society. The Liber Usualis provides most of the chants necessary for those who want to sing it.

It's main disadvantage is that the breviary itself does not come cheap. There is however a free downloadable app available on itunes for it available for it that may suit many people.

The other problem is that in my view at least, the psalm distribution it uses simply doesn't work all that well - some of the repetitions it eliminated (such as of Psalm 50 and the Laudate psalms at Lauds each day) are actually quite important spiritually. And few of the individual hours or days have much internal coherence in my view.

By contrast, the much more ancient Office of St Benedict seems to me to provide a psalm cursus that is both closely linked to the spirituality of the saint's Rule, and is a tightly constructed masterpiece.

There are some issues, though, around the use of the Offices of the religious orders that are worth touching on, including how much of it to say - and who (if anyone save for professed religious) is actually entitled to say it. So more on the Offices of the religious orders in the next post in this series.